“the play’s the thing/Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.”—Hamlet (2.2.539-40)

One of my teachers, an American director named John Dillon, once told me every scene in a play is a chase scene. I vaguely remember in his “Directing Shakespeare” course at Sarah Lawrence (where I did my MFA) as actors, us literally running around the theatre chasing each other while we said our lines. Over the years, the full extent of this provocation has unfolded to me time and again. In the theatre, someone is always actively pursuing something or someone. It’s gameplay.

In these initial Hamlet rehearsals, each time we’ve put a scene on its feet David has asked the ensemble, “What’s the game of this scene?” which usually provokes a series of offers. For example, when rehearsing 1.1 with the sentinels and Horatio on the battlements these are some of the potential games we came up with:

-“Who’s the best security guard?”

-“The first one to be scared is a dick”

-“Trauma topping” (i.e. who has the worst ghost story)

Testing these games in rehearsal is fun, active, and adds dynamism to the scene. Everyone wants to win.

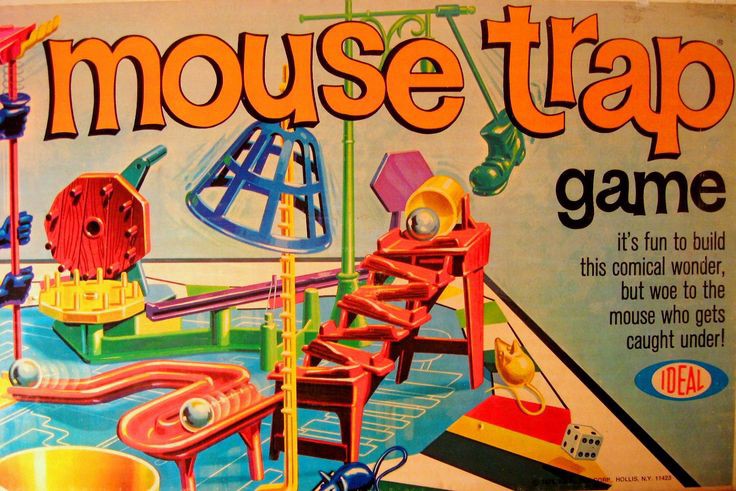

The biggest game in Hamlet is the one she plays with Claudius throughout the entire play, ending with the final fencing match. One move is the play-within-a-play, The Murder of Gonzago, which Hamlet inserts lines into so as to ensnare Claudius into exposing his guilt. Hamlet’s adaptation goes beyond writing additional lines to re-titling the play. Claudius asks, “What do you call the play?” to which Hamlet responds, “The Mousetrap.” A mousetrap is of course a device for catching small rodents. A“mouse” could also figuratively mean a person who is small, timid, weak, or insignificant. All Claudius need do is take the bait, and it will snap, rendering him completely powerless and effectively destroying him. [Another interesting view on “mousetrap” is that the word can also be a euphemism for female genitalia, vagina, and Hamlet uses repeated sexual language throughout this scene.] The game seems to be simple: catching consciences. What’s more fun to probe than naming the game is considering the game pieces. Why a play? What aspects of theatre make this game work? It is worth noting that in this instance it is a game played not only between actors but also between actors and audiences.

Here are a few thoughts (but I’ll leave them as thoughts so you can play the game yourself):

Hamlet says, “The purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold as ’twere the mirror up to nature: to show virtue her feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”

Theatre is a public gathering, a shared experience.

Theatre is an act of remembrance. Literally, to “re-member,” as in to reconstruct, put back together, animate.

Theatre is empathy.

Theatre is confession.

Theatre is reflection.

Theatre is storytelling.

Theatre is life.

We could say a thing lives or dies by the story that is told.

(Source: https://herebythemaverick.wordpress.com/2017/10/02/hamlet-caught-in-mickeys-mouse-trap/)